Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o’er-wrought heart and bids it break.

Macbeth, Act 4, Scene 3

Grief often reshapes the way we see art, and sometimes it reveals the hidden stories behind the works we think we know. Reading Hamnet made me reconsider Hamlet not as a monument of genius alone, but as a vessel of private sorrow.

Shakespeare writes Hamlet while still moving through the dense, unspoken fog of losing his son, Hamnet. Agnes, his wife—so attuned to the rhythms of the earth, to the pulse of living things—cannot decipher the way her husband grieves. To her, his composure feels like distance. His return to London, his relentless work on the stage, his immersion in characters and plots all seem like evasions, as though he has shunned their shared sorrow. While she mourns with her hands, her breath, her body, he mourns in silence, in absence, in the strange inwardness of a man who turns pain into language.

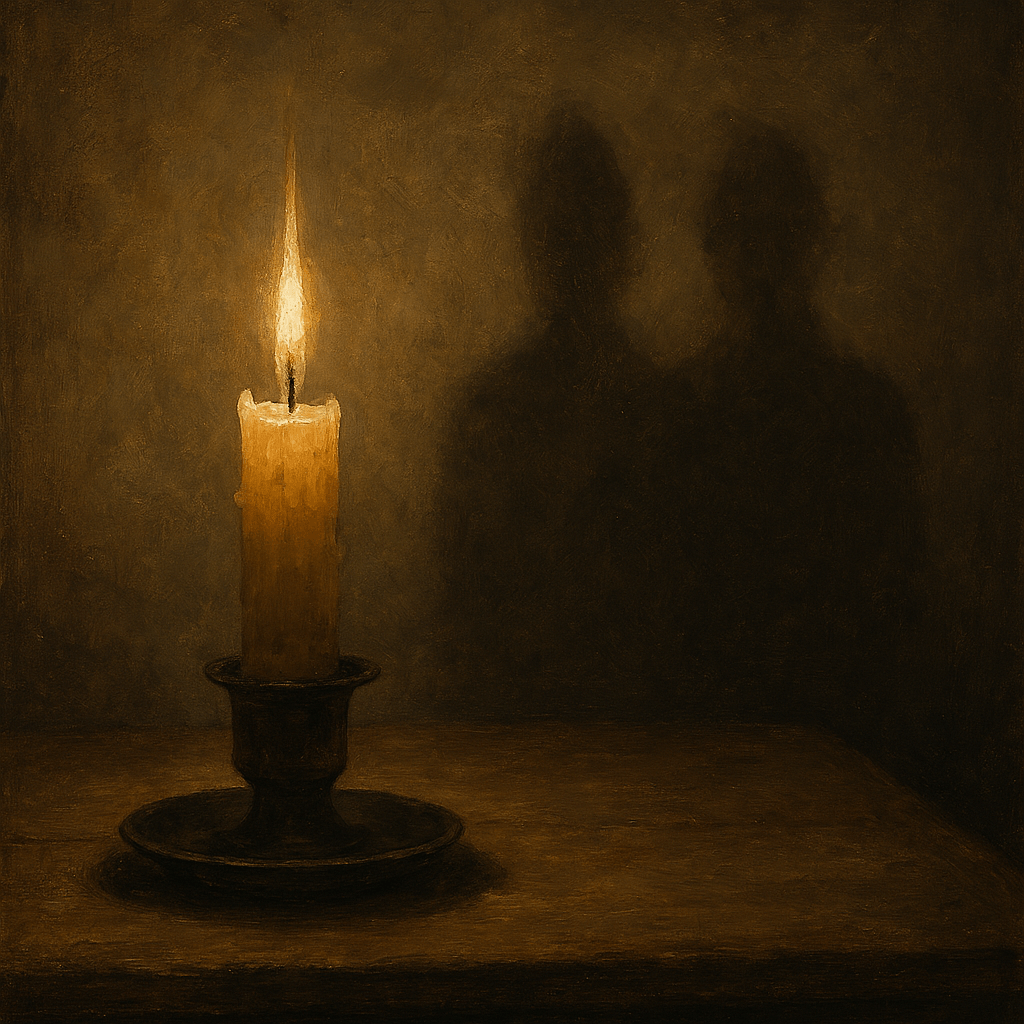

For a long time, Agnes believes he has abandoned the grief that has hollowed her out. She imagines him thriving among actors and patrons, untouched by the loss that has reshaped her world. But when she travels to London and sits in the dimness of the theatre to watch Hamlet, something shifts. Onstage, she sees a ghostly father summoned from death, a son who cannot release the past, a family fractured by absence. In those figures—so distant from her life yet uncannily familiar—she recognizes the contours of her own mourning.

Only then does she understand: her husband has not escaped their grief. He has carried it with him, threading it into the fabric of the play. The ghost onstage is not merely a dramatic device; it is the echo of their lost child, the shape of a sorrow he could not speak aloud. Through Hamlet, he has given form to the ache that bound them both. Agnes realizes that the play is not a departure from their loss but an offering—a way of holding Hamnet close, of keeping him alive in the only language Shakespeare knows how to wield.

Art holds a central, almost sacred place in Shakespeare’s life. We often imagine the Bard spinning his plays out of sheer, unbounded imagination, as though genius alone were the source of his creativity. But that view does not quite do justice to the depth of his artistry. In the case of Hamlet, it is grief—raw, bewildering, and transformative—that becomes the true engine of creation. The death of Hamnet does not silence Shakespeare; instead, it is transmuted, refined, and sublimated into one of the greatest tragedies ever written.

The beauty of art, in this sense, proves more enduring than any epitaph or ritual gesture. A gravestone marks a life; a play reanimates it. Through Hamlet, Shakespeare not only memorializes his son but also inscribes himself into the fabric of cultural memory. The tragedy becomes a double act of preservation: the child who died young and the father who mourned him both find a kind of immortality in its lines.

Language becomes the vessel through which grief is transformed. Instead of loud cries or outward displays of sorrow, the pain distills into quiet, resonant meditations on death, memory, and the fragile condition of being human. The play’s reflections—its ghosts, its hesitations, its questions—carry the weight of a father’s loss without ever naming it directly.

In this way, art becomes a means of transcending death. What is lost in life is carried forward in language. What cannot be restored in the world is reimagined on the stage. Through the alchemy of creativity, Shakespeare turns grief into something enduring, something that continues to speak across centuries. And in that transformation, both he and Hamnet step beyond the limits of mortality.